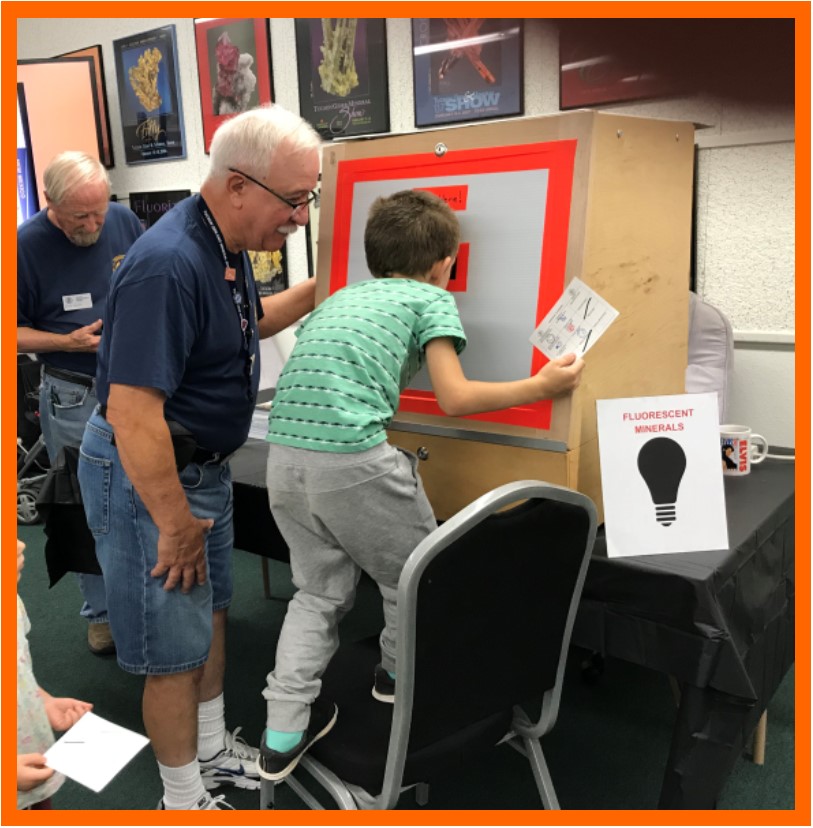

After taking an earth science trip around the room, they got to go to the “spin the wheel and win a prize!” We had mineral specimens, hats, gold pans, 10x eye loops, lanyards, bags, and a host of other fun things to choose from. It was fun listening to hoots and hollers when the “wheel” landed on a “TGMS Gold Seal.” That’s when they got to choose their OWN very special mineral specimen.

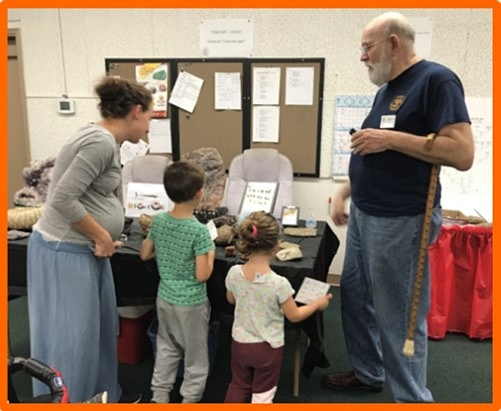

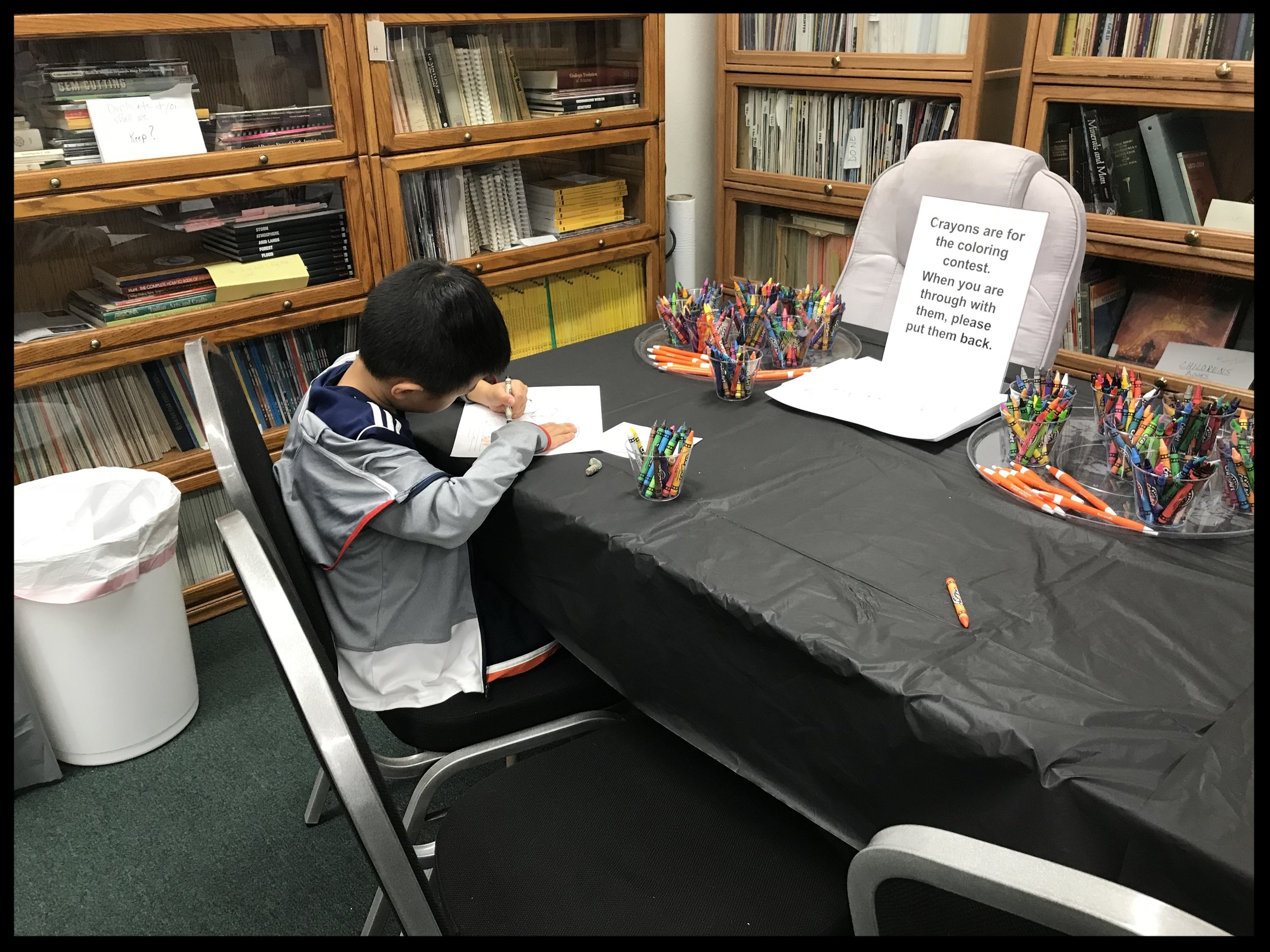

We had over 250 people participate. There were parents, grandparents and children that came to visit us on that fun and rainy day. We feel that we had a pretty successful event. We received lots of “Thank You’s”, donations to the cause and we even sold a few TGMS products. By all accounts … it was a SUCCESS! AND we all had fun!

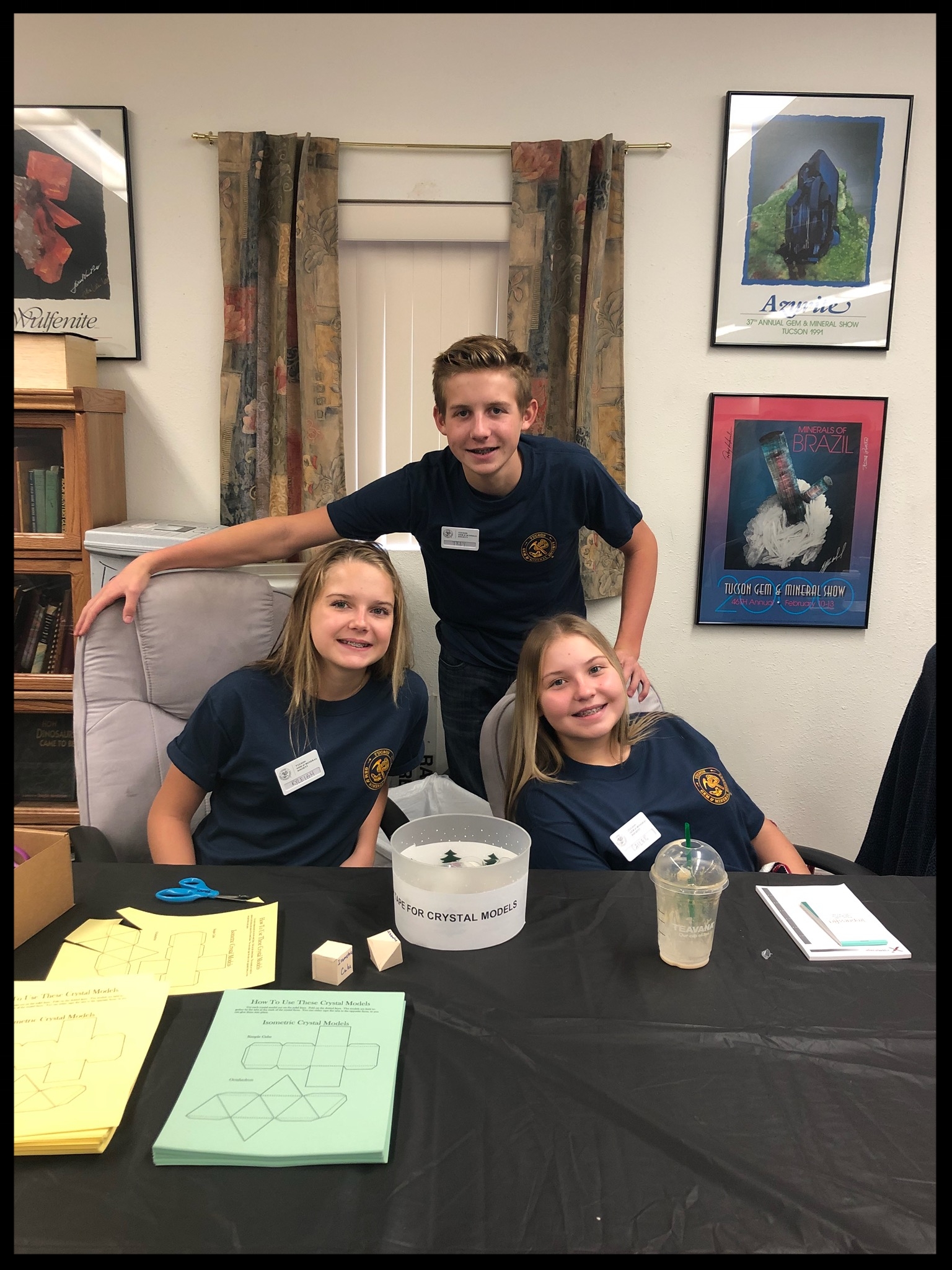

A big “THANK YOU” goes out to: Tim McClain, Ron Gibbs, Mark Ascher, Brad Gibbs, Victoria Fila, Rose Marques, Kerry Towe, Mike Hollonbeck, Diane Braswell, Mary Kirpes, Kent Stauffer, Linda Stauffer, Daniel Kirpes, Christine Marikos, Mark Marikos, Ortrud Schuh, Louis Pilll, Bob Melzer, Bill Shelton, Myles Isbell, Jennifer Isbell, Dick Gottfried, Linda Oliver, Bre Oliver, Trey Oliver, Kyleigh Oliver, Cailen Oliver, Molly Radwany, Beverly Lynch, Susanne Collier, Marilyn Reynolds, Bruce Kaufman, Warren Lazar, Cathy Logan, Pat McClain.

So onward and upward to our next community outreach program and, hopefully, we will do this very special event again!